Cash can be used by everyone, regardless of age, gender or financial situation. Because it is not linked to the identity of the users, cash does not discriminate against its users.

One obvious feature of cash is that it can be used by all, regardless of age, gender or financial situation. In many cases, people do not have access to alternative instruments or to banking services in general. According to the World Bank1, only 50% of the world’s population aged 15 years or older have an account at a formal financial institution. The majority of the “unbanked” live in developing countries, but even in the US 7.7% of households, amounting to 9.6 million households, had no account in a formal financial institution in 20132. Children constitute another group with limited access to non-cash payments; according to the United Nations Population Estimates3, 27% of the world population was under 15 years old in 2011, representing 1.8 billion children.

Michael King4 has established that in Nigeria, where only 30 % of the population above 15 is banked, the number of official documents required to open an account reduces the likelihood of being banked. According to UNICEF5, worldwide 230 million people under the age of five – around one in three – have never been formally registered and therefore do not officially exist.

There are numerous other groups which have limited or no access to alternative payment systems. In some countries, women are not entitled to open a bank account. For others, non-cash payment systems are challenging to use; particularly for vulnerable people such as the illiterate, the visually impaired, and persons with mental disabilities.

Cash can also be accepted by all merchants. It does not require a bank account, registration with a payment scheme, a device such as a POS terminal, or access to a network. As a result, the vast majority of merchants worldwide accept cash, whether they are large or small, including those in remote locations without access to phone, internet or electricity.

Politics can interfere with the acceptance of other payment methods. In 2010, Visa, MasterCard and PayPal blocked payments to WikiLeaks, a not-for-profit media organisation that had published US diplomatic cables and classified information. In 2014, following the annexation of Crimea, Visa and MasterCard stopped processing transactions for several Russian banks in line with US sanctions6.

Alongside the fact that it can be used by everyone, cash does not discriminate between users. Payment service providers tend to segment their markets according to income levels; the more affluent customers are offered premium solutions with an ever-increasing range of benefits and rewards. These products also become a status symbol. Mashreq Bank in the UAE has launched its exclusive Solitaire7 credit card, with a certified diamond embedded in it. Those who do not have access to premium cards may feel ostracised.

Another illustration of discrimination concerns welfare organisations that attempt to replace cash payments with alternative instruments. In 2009, The British government introduced the Azure payment card for people who have been refused asylum. The card is only accepted at designated retailers and is intended to cover food and essential toiletries only. According to a study published by the Asylum Support Partnership Team8, “the payment card causes anxiety and distress amongst users and contributes to the stigmatisation of asylum seekers.” In particular, 56% report feelings of anxiety and shame when using the card and 38% report being ill-treated by shop staff.

Cash can be used for a broad range of transactions of different value, via different channels and between different parties. It is a “general purpose” instrument.

Retail payments are increasingly diverse, involving a growing number of variables: the value, the frequency, the actors involved (business, consumer, and administration), the spending category, the channel used, the device, etc. The result is a complex matrix of transaction types.

At the same time, payment instruments are growing increasingly specialised, dedicated to a specific channel such as online payments, a specific spending category such as travel, or a specific merchant. In London, the Oyster card has been introduced for electronic ticketing on public transport; it has been designed to reduce the use of paper tickets and phase out cash transactions. It is a stored-value card which can be loaded online, at payment card terminals, or with cash. In June 2013, it was revealed that nearly £100 million of passengers’ money is lying on dormant cards9. Similarly, dollars loaded on Starbucks cards totalled $1.4 billion in 201410. Other instruments are used specifically for online payments or for peer-to-peer transactions.

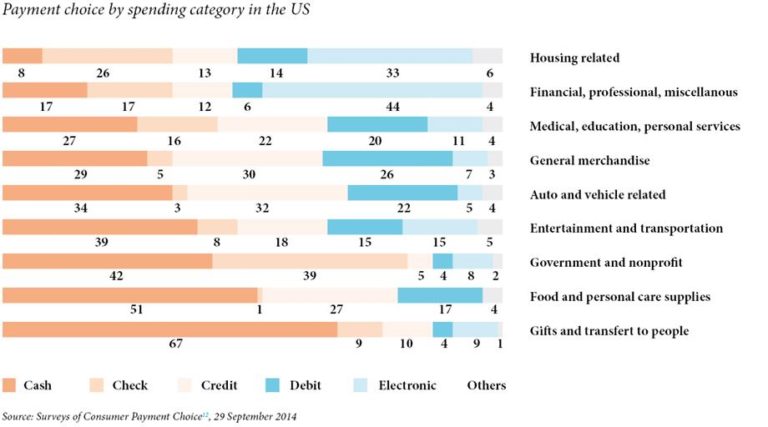

Cash on the other hand can be used for a broad range of transactions. Numerous consumer payment surveys have shown that cash is widely used for low-value transactions. In the US, according to the 2012 Consumer Payments Diary 11 (see below), 66% of transactions under $10 are settled in cash. But 9% of transactions over $100 are also paid in cash. Looking at spending categories, cash is the first or second most widely used instrument for all categories except housing-related items.

Cash is widely used in traditional channels such as face-to-face payments in a shop, or person-to-person payments, but is also widely used for other transactions.

According to the World Bank, remittances – international money transfers often initiated by migrant workers – totalled $582 billion in 201412, involving some 232 million migrants. They represent an essential source of funding for developing countries and are three times larger than official development assistance. Remittances rely largely on cash which is used at one or both ends of the transaction: cash-to-cash, account-to-cash and cash-to account amount to 56% of transactions as illustrated below. Cash products are also one of the most cost-effective ways to send money.

Cash is also widely used for consumer-to-machine transactions. In Europe alone, 3.77 million vending machines generate an annual turnover of €11.3 billion. The majority of these machines accept cash.

Cash is also used for online transactions. In 2012, the world’s largest retailer, Walmart launched ‘Pay with Cash’13, which enables its customers to shop online and pay with cash at stores. “Our new ‘Pay with Cash’ offering makes it easier for our customers to shop the way they want, where they have access to a broader product selection at Walmart.com coupled with the convenience of payment and shipping as they want.” said Joel Anderson, president and CEO of Walmart.com. In the UK, according to research from online payment services provider, Ukash14, one third of online shoppers would prefer to use cash when buying from websites. And 18-24 year-olds are the most likely to want to pay with cash online, with 52% of this group saying they would prefer this method. In India, the taxi-hailing application, Uber offers users the option to pay in cash15.

Cash does not rely on a technology infrastructure. It works anywhere, anytime and for everyone. It is not subject to technological breakdowns or failures.

Banknotes and coins enable payments between consumers, businesses and other economic agents and are not dependant on infrastructure. Most alternative payment instruments rely on some form of technology. A card transaction, for instance, requires a cardholder with an active card and a merchant with a compatible payment terminal, as well as a back-office infrastructure to process the transaction. This has several implications.

Cash payments work anywhere, at any time and with all economic agents. The technology is embedded in the notes and coins. The world is increasingly connected and internet access continues to make significant progress. The International Telecommunication Union estimated16 that, at the end of 2013, 2.7 billion people worldwide used the internet. This means that 4.4 billion people are not online. Figures are even more striking with mobile phones: 6.8 billion mobile cellular subscriptions existed in 2013, or almost one per person! However, in 2012, only half of the world’s population was covered by a 3G network, which qualifies as mobile broadband. Even in those countries which have good coverage, there are areas of limited access such as mountain regions or on trains.

There is inevitably a cost in adopting a payment system, partly related to the infrastructure. A merchant willing to accept payment cards needs to purchase or rent a payment terminal. For large merchants, these costs are easily depreciated over the high volume of transactions but the business case is far more complex for small merchants and start-ups. New businesses can begin operations by accepting cash only, for which no prior investment is required, and only at a later stage, depending on customer demand, choose which other payment options to adopt.

The development of payment infrastructure is largely dependent on network externalities. This means that the value of a payment card to its holder depends on the number of merchants who accept it and the value of the card to a merchant depends on the number of cardholders. As the range of payment instruments grows wider, the network effect increases and makes the launch of new instruments more challenging.

Apple launched Apple Pay in the US at the end of 2014; it enables iPhone 6 users to make payments in stores using NFC (near field communication) technology. Shortly after, a consortium of leading retail companies such as Walmart, 7-eleven, Sears and Shell announced the launch of CurrentC, a mobile payment app based on QR codes. The competition between the two products has been described as the “clash of the titans. It’s Betamax vs VHS”17 according to Forbes journalist Clare O’Connor.

Lastly, no technology is exempt from breakdown or failure. At the London Olympics in 2012, the payment systems failed during football events at Wembley18 despite Visa being one of the global sponsors of the games. Spectators had no option but to pay in cash as payment terminals stopped working. On 24 December 2013, the Belgian card network failed leaving millions of Belgians unable to pay in stores or online or to withdraw cash from ATMs19 at the peak of Christmas shopping. In June 2008, the Bank for International Settlements published a report20, which concluded that the risk of failure within the world’s payment and settlement systems is growing because they are becoming more interconnected. The report recommended that banks and payments operators provide better protection against a failure of the financial systems in their stress tests, risk controls, funding requirements and crisis-management plans. However, the global financial crisis, which erupted in October 2008, has likely delayed the achievement of these objectives.

Its legal tender status gives cash a robust legal framework and facilitates its acceptance and usage. However, restrictions on the use of cash are increasing.

Legal tender has been developed alongside the evolution of notes and coins. In the 13th century, Mongol Emperor Kublai Khan, the first to introduce paper notes and then fiat money, declared his currency the only acceptable currency of the land. He banned the use of gold and silver, as well as private vouchers and coupons that could be a threat to the new currency21.

Legal tender is a legal concept and by definition, depends on the legal framework of each country. For example, the legal tender status of euro banknotes is laid down in Article 128 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union; however member States have very different national legislative provisions in relation to legal tender. Consequently, the European Commission issued a recommendation in 201022 to clarify the scope and effects of legal tender in the euro zone. The recommendation lays down ten guiding principles:

- The concept of legal tender should rely on three main elements: a mandatory acceptance of banknotes and coins, for their full face value, with a power to discharge debts.

- The acceptance of payments in cash should be the rule: a refusal is only possible if grounded on reasons related to the ‘good faith’ principle (for example, if the retailer does not have enough change).

- Similarly, the acceptance of high denomination banknotes should also be the rule.

- No surcharges should be imposed on payments in cash.

- Member States should refrain from adopting new rounding rules to the nearest five cent.

- Member States should take all appropriate measures to prevent euro collector coins from being used as means of payments.

- Stained banknotes should be brought back to the National Central Banks as they might be the product of a theft.

- Total destruction of banknotes and coins by individuals in small quantities should not be prohibited.

- Mutilation of banknotes and coins for artistic purposes should be tolerated.

- The competence to destroy fit euro coins should not belong to national authorities in isolation anymore.

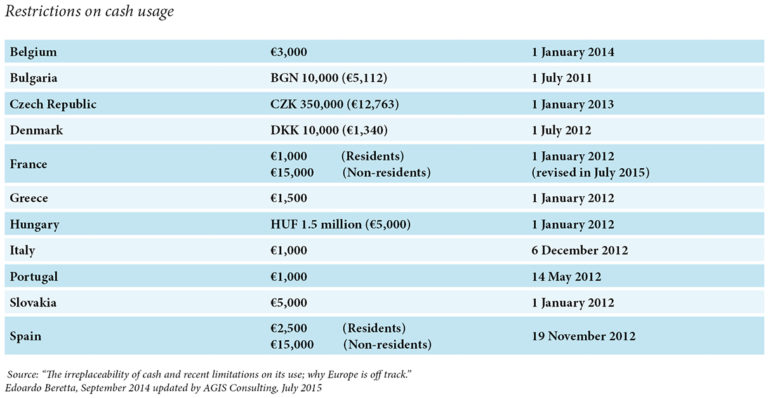

In principle, legal tender provides a secure legal framework for notes and coins and ensures its widespread acceptance. In practice, it appears that the above guidelines are not enforced strictly. Several countries, including Finland and the Netherlands, have adopted rounding rules whereby amounts are rounded to the nearest five cents in order to reduce the handling of one and two cent coins. Across Europe, some retailers refuse to accept the highest denomination notes – €200 and €500. In October 2014, a customer of French supermarket chain Leclerc was taken into police custody after trying to pay with a genuine €500 note23. The cashier and the police suspected the note was a counterfeit. In the Netherlands, several stores no longer accept cash payments. Several countries have imposed caps on cash payments, essentially in order to reduce tax evasion. Payments exceeding these amounts cannot be settled in cash.

Most countries have defined legal tender in their central bank’s mandate or in their legislation. Singapore was the first country to announce the adoption of a form of electronic legal tender as early as 1998. According to Low Siang Kok, Director of Quality at the Board of Commissioners of Currency Singapore24, “BCCS envisages that an electronic legal tender system would reduce the cost of handling physical cash, improve the efficiency of business transactions and boost the cashless business environment for Singapore. It would also support the government’s drive to turn Singapore into a cashless society. At its strategic planning seminar in 1998, BCCS set as its corporate vision the introduction of a Singapore electronic legal tender (SELT) within 10 years.” However, in 2014, the SELT project no longer seems to be on the agenda and the Singapore Monetary Authority continues to issue banknotes, which increased in value by 6% in 2012.

In 2014, the Central Bank of Ecuador announced plans to create a virtual currency, which would be used alongside the U.S. dollar, which is legal tender in Ecuador25. The first virtual money accounts were opened in December 201426. Following the banking crisis of 1999, the Ecuadorian peso sucre banknotes lost legal tender status in favour of the US dollar. Today, Ecuador only issues centavos coins.

Besides payments, a key function of money is to store value. Cash provides a liquid and secure store of value. The 2008 global financial crisis clearly illustrated its importance.

Payment is only one of the functions of cash. A second essential function is to store value.

Banknotes are a financial asset and although they do not bear interest, they offer liquidity and security.

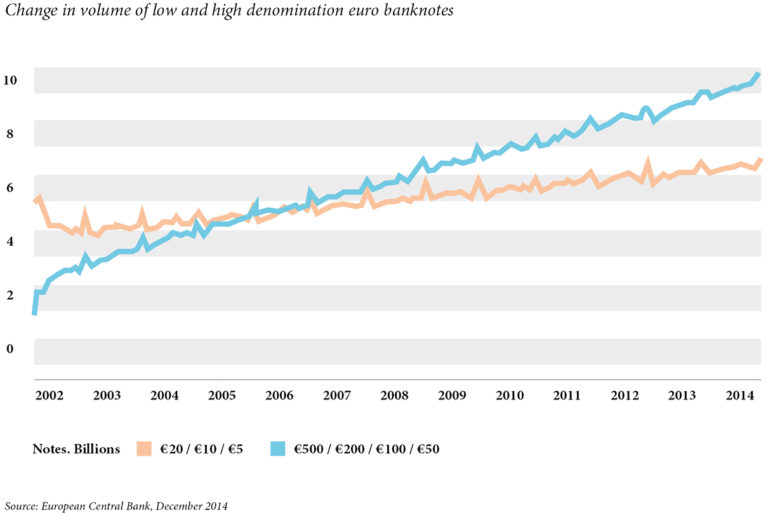

Several studies have measured the share of hoarded banknotes versus transactional banknotes. Helmut Stix has estimated that roughly 10% of cash in circulation was used for transactions in Austria in 200427. B. Fischer, P. Köhler and F. Seitz28 estimate that around 25 – 35% of all currency in circulation in the euro zone is used for domestic transactions. The remaining 65 – 70% is either hoarded or held abroad.

The mix of denominations in circulation provides a rough assessment of the importance of hoarding. In Switzerland, the CHF 1,000 note, which is one of the highest denominations in the world, represents 61% of the value of notes in circulation29, but this note is rarely used in daily transactions.

The store of value function also largely explains the international demand for some currencies. Estimates by the US Federal Reserve suggest that as much as 60% of US currency is held overseas30. In the case of the euro, an estimated 25% of the euro currency and possibly more was circulating outside the euro zone at the end of 201331. For foreigners, an international currency represents an asset which is liquid, secure and stable in value. These attributes are often not provided by their own currency, particularly after periods of economic instability.

Interest rates are a key factor in explaining currency demand and, in particular, demand for hoarding. Lower interest rates reduce the opportunity cost of holding cash and make it more attractive. Another factor is the level of confidence in the banking and financial system. According to Tom Cusbert and Thomas Rohling32, currency demand in Australia increased abnormally fast in late 2008, following the collapse of Lehman Brothers, and resulted in a 12% rise in the value of banknotes. Around 20% of this can be attributed to the lowering of interest rates and the increase in income from the government stimulus. The remaining 80% of the rise may be due to an increase in precautionary holdings in response to uncertainty in the financial sector.

Using survey data from ten Central, Eastern and South-Eastern European countries, Helmut Stix has analysed why households in transition economies prefer to hold sizeable shares of their assets in cash at home rather than in banks33. The paper documents the relevance of this behaviour and shows that cash preferences cannot be fully explained by whether people are banked or unbanked. The analysis reveals that a lack of trust in banks, memories of past banking crisis and weak tax enforcement are important factors. Moreover, cash preferences are stronger in dollarised economies where a “safe” foreign currency serves as a store of value.