Humanitarian Financial Assistance – How to Reduce Risk and Improve Value

But CVA programmes introduce a whole range of additional fiduciary risks for aid organisations – from a donor perspective, fiduciary risk management means that funds entrusted to an aid organisation are “not used for their intended purpose, do not realise their full value-for-money, or cannot be properly accounted for” (UK-FCDO, 2020) – which have to be integrated into programme design and negotiated with financial service providers and other partners in advance if better value-for-money is to be achieved.

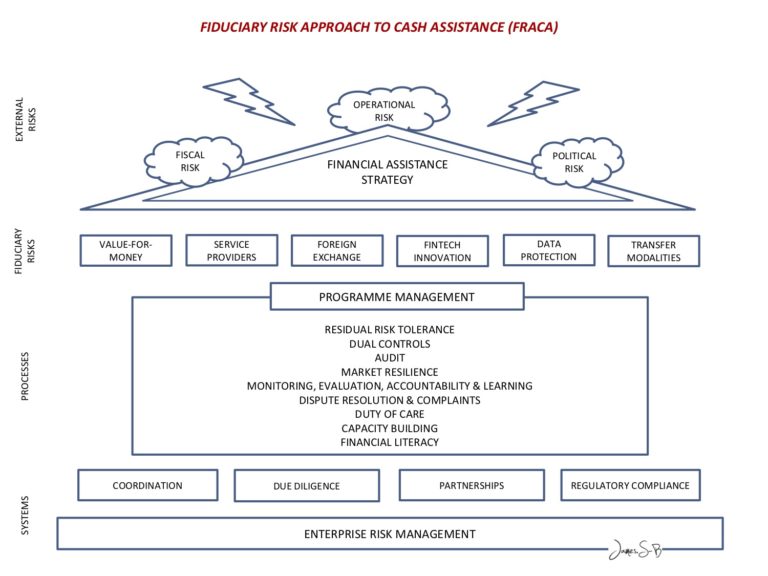

If aid organisations and their donors want to improve the social utility and cost-effectiveness of their CVA programmes, they could consider applying an integrated fiduciary risk management model (See Figure 1) which includes the following cost components:

Fig. 1: The Fiduciary Risk Approach to Cash Assistance (FRACA) Model

Economies-of-Scale: As DFID one famously said in its review of the ‘one cashMoney in physical form such as banknotes and coins. More platform’ in Lebanon in 2016, “It doesn’t take twenty NGOs to load a pre-paid card.” In Jordan, pooled funding saw transaction costs fall from an average of 3.25% to 1.67% as a direct result of fee negotiations with issuing banks and other financial service providers being conducted collectively through a single focal point. The rapid evolution of financial technology now allows mobile moneyFrom the Latin word moneta, nickname that was given by Romans to the goddess Juno because there was a minting workshop next to her temple. Money is any item that is generally accepted as payment for goods and services and repayment of debts, such as taxes, in a particular region, country or socio-economic context. Its onset dates back to the origins of humanity and its physical representation has taken on very varied forms until the appearance of metal coins. The banknote, a typical representati... More aggregators to provide for multiple donors and multiple logos while using a single platform … which means there is little reason for organisations not to collaborate.

Consolidation: Pooling financial resources shares – and therefore dilutes – fiduciary risk. It also eases the burden of complying with international counter-terror and anti-money-laundering regulations.

Advocacy: Discussions with central banks over issues connected with de-risking and regulatory compliance are taken much more seriously when multiple agencies lobby coherently and collectively through a single representative. For example, such a joined-up approach saw mobile ATMs re-introduced into Jordan’s refugee camps.

Breakage: The term is banking jargon used to describe revenue gained by financial service providers through un-redeemed money loaded onto pre-paid cards that is never claimed … in this case, by humanitarian beneficiaries. Once uploaded onto recipients’ pre-paid cards or mobile wallets, digital cash transfers represent an off-balance-sheet liability. It is assumed that once funds are uploaded they will be spent in full. But they’re not. And, unless specified otherwise in the framework partnership agreement, balances are (quite legally) retained by the FSP. Since this can amount to 5% or more of the total cash transferred, the sums involved can be substantial.

Interest: When pre-paid cards are used for the provision of cash assistanceThe term cash assistance refers to direct cash transfers to individuals, families and communities in need of humanitarian support in lieu of in-kind commodities or direct service delivery. The term can be used interchangeably with ‘cash-based interventions’ (CBI), ‘cash transfer programming’ (CTP), ‘cash and voucher assistance’ (CVA), and ‘cash-based programming (CBP)’. It does not include fund transfers from donors, payment of incentives to the staff of local authorities, paymen... More, interest accrues to the issuing bank. When corporate debit cards are used, interest accrues to the donor or partner organisation as funds are only dispersed when the card is used.

Foreign ExchangeThe Eurosystem comprises the European Central Bank and the national central banks of those countries that have adopted the euro. More: International aid organisations rarely, if ever, challenge the bid-offer spread quoted for international money transfers, or attempt to negotiate volume discounts when converting currencyThe money used in a particular country at a particular time, like dollar, yen, euro, etc., consisting of banknotes and coins, that does not require endorsement as a medium of exchange. More locally. Local variances are also irrelevant as long as financial control protocols are followed at headquarters level. In the Yemen during the 12-month period 2017 to 2018 this led to aid agencies unnecessarily paying over $48 million in transaction fees by failing to capitalise on a floating exchange rateThe rate at which one currency will be exchanged for another. More (CashCap, 2018).

Multiplier Effects: The recirculationThe right to recirculate banknotes that have been checked for authenticity and sorted for fitness by banks and cash-in-transit companies. The right is normally based on rigorous rules established by the central bank. More of physical currency in local markets exerts economic multiplier effects that can more than double the face-value of cash assistance over its digital equivalents (ODI, 2015).

Discounting: Local goods purchased in local markets with physical currency (cash-in-hand) tend to be cheaper than those purchased through ‘restricted’ or digital mechanisms as the merchant can rebate the cost of electronic paymentA transfer of funds which discharges an obligation on the part of a payer vis-à-vis a payee. More fees (Oxford University, 2020).

Regulatory Compliance: By law, financial service providers are obliged to conduct ‘know your customer’ (KYC) due diligence on each potential customer. Additional legal measures covering anti-terror, anti-money-laundering and data protection have also been introduced recently. In crisis situations, at least some of this process is carried out by the aid agency partner, thus saving the service provider the cost of doing so. The overall cost for commercial KYC processing ranges from $15 to $130 per background check and takes an average of 48 days (Consult Hyperion, 2019).

Cost of Customer Acquisition: Cash assistance programmes deliver new customers to the issuing bank effectively for free, thus saving them one of their biggest business costs, the cost of customer acquisition and retention. This ranges from $1,500 per customer for a large US or European bank to about $250 for a smaller bank in a lower-income country (Stratifi, 2019).

Interchange: ‘Interchange’ refers to the fee charged by the issuing bank to the acquiring bank to cover their part in the clearing and settlementThe discharge of an obligation in accordance with the terms of the underlying contract. In e-transfers the settlement may take days, whereas cash settlements are instantaneous and irreversible. More process. This fee is set by the card networks, not the banks. Depending on the scale of the programme, it can be negotiated in humanitarian situations with the support of the national central bank. Long an industry secret, these fees have begun to be regulated with the result that interchange fees are beginning to come down. However, there are signs that ‘card scheme fees’ have risen in order to compensate for this reduction.

With the Fiduciary Risk Approach to Cash Assistance (FRACA) model in mind, I suggest that the following recommendations, if systematically applied at programme or country level, would help achieve better value-for-money for humanitarian financial assistance programming while at the same time reducing fiduciary risk:

- Hire retail finance consultants from the cash and payments industries – not commercial banks or the aid sector – when constructing business cases, negotiating framework partnership agreements, and managing fiduciary risk compliance during programme implementation.

- Transfer funds to beneficiary mobile wallets or pre-paid cards on a just-in-time basis.

- Encourage consolidated (pooled) funding at national level.

- Become proactive members of local Cash Working Groups and advocate collectively through the Humanitarian Coordinator.

- Ensure reimbursement of outstanding balances (breakage) when programmes end and include such provisions in framework partnership agreements.

- Where debit cards are viable, us the corporate rather than pre-paid version.

- Monitor local ForEx rate volatility and agree daily rates together. Ensure currency conversion uses that day’s local rate, not the interbank ‘spot’ rate quoted.

- Work with national central banksIn general, the expression refers to the central banks of different countries. More to ensure liquidityDescribes the extent to which assets or rights can be converted into cash without causing a significant decrease in the asset’s price. Accordingly, liquidity is often inversely proportional to the profitability of the asset and involves the trade-off between the selling price and the time needed to convert it to cash. In finance, cash is considered the most liquid asset and cash is sometimes used as a synonym for liquidity (e.g. cash reserves; cash pooling…). More in money supply so that cashing-out drives local multiplier effects.

- Collectively negotiate KYC and Customer Acquisition rebates from issuing banks.

- Collectively negotiate interchange rates with card companies.

For more information on cash in crises situations, please check our Cash and Crises page.