Increasing card usage will not curb the shadow economy

In September, The Economist published an article entitled Informal payments cost governments hundreds of billions in revenue each year. The article is illustrated with a striking chart ‘demonstrating’ the negative correlation between the shadow economy and the number of card payments per person.

The chart is indeed striking, but it does warrant a few comments before jumping to the conclusion that encouraging electronic payments is sufficient to reduce the size of the shadow economy.

Firstly, estimating the shadow economy is complex. The data used in this chart is based on a theoretical method to estimate the shadow economy but it remains an estimate. The authors Medina and Schneider conclude: “An internationally accepted definition of the shadow economy is missing. Such a definition is needed in order to make comparisons easier between countries and methods, and also to avoid a double counting problem.” In a separate study ,Prof. Schneider reached the conclusion that “cashMoney in physical form such as banknotes and coins. More has a minor influence on the shadow economy, crime and terrorism, but potentially a major influence on civil liberties.”

Secondly, let us not confuse correlation and causation. We can assume that some informal transactions are settled in cash to avoid leaving a trace for tax authorities. In other terms, a smaller shadow economy may lead to a higher use of card payments but the opposite is not true, as the Economist wrongly suggests. Increasing card usage does not shrink the shadow economy. The British Access to Cash Report concludes: “We don’t disagree with these points, and many in the UK agree: 36% believe that a cashless society would reduce crime. There are other considerations, though, such as people working legally in the cash economy: some window cleaners and gardeners operate below the tax threshold, and many feel the cost of card terminals is prohibitive. We also believe that crime will always find a way: for example, goods are bartered in prisons instead of cash.”

Thirdly, the correlation is far from perfect as illustrated by many outliers in the chart. The chart shows that Germany has a smaller shadow economy than Sweden (11.97% vs 13.28) but has about 5 times less card payments per person. Estonians make almost as many card payments as the Dutch, but the shadow economy is three times more important.

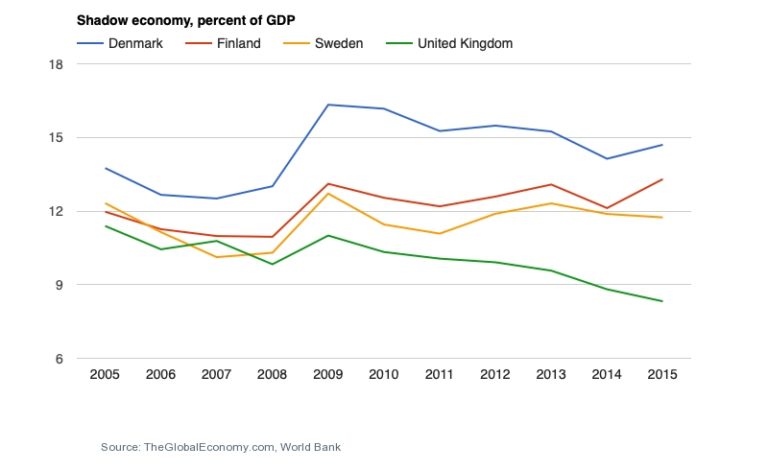

Another way of looking at this is to look at the evolution of the shadow economy over the past decade. The case of Sweden is particularly interesting as it is well documented that Sweden has seen cash in circulationThe value (or number of units) of the banknotes and coins in circulation within an economy. Cash in circulation is included in the M1 monetary aggregate and comprises only the banknotes and coins in circulation outside the Monetary Financial Institutions (MFI), as stated in the consolidated balance sheet of the MFIs, which means that the cash issued and held by the MFIs has been subtracted (“cash reserves”). Cash in circulation does not include the balance of the central bank’s own banknot... More decline over the past decade by approximately 30% in value. The shadow economy has remained stable over the period.

What are the conclusions in terms of policy? The Economist concludes “One way, then, to shrink the shadow economy is to encourage electronic payments.” Banks and PaymentA transfer of funds which discharges an obligation on the part of a payer vis-à-vis a payee. More Service Providers will certainly support this view. But why should all individuals be prevented from using cash only because a minority uses it improperly? It is noteworthy that ten countries in the EU which have imposed limitations on cash payments are all positioned at the four top left quadrants of the chart, with low card usage and high shadow economies.

Recently, Nigeria, Italy and Mexico have announced policies aimed at reducing cash usage or promoting digital payments. It is doubtful they will succeed in curbing the shadow economy but they will restrict the freedom of those who prefer, or need to pay by cash. In March, the Deutsche Bundesbank concluded that “there is still a lack of empirical evidence as to whether measures such as abolishing large-denomination banknotes or introducing upper limits for cash payments would, in fact, be an effective means of combating tax evasion and other criminal activities.”