CBDC: More Bark than Bite?

Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC)A digital payment instrument, denominated in the national unit of account, and a direct liability of the central bank, like banknotes. A general purpose CBDC can be used by the public for day-to-day payments like cash. More is a hot topic in the payments world.

The Bank for International Settlements has been closely monitoring how central banks have been researching and exploring the issue since 2016. The Bank of Finland, however, reminds us that the topic has been discussed for 30 years, and the Avant smart card system developed by the Bank in the 1990s can be considered the world’s first CBDC.

What is a CBDC? It is “a digital representation of sovereign currencyThe money used in a particular country at a particular time, like dollar, yen, euro, etc., consisting of banknotes and coins, that does not require endorsement as a medium of exchange. More that is issued by a jurisdiction’s monetary authoritySee Central Bank More and appears on the liability side of the monetary authority’s balance sheetA piece of paper or substrate of 800 mm by 700 mm, on which banknotes are printed. The “sheet to sheet” printing technique is the most widely used in printing of banknotes, but the roller printing technique also exists. More” (Kiff et al. IMF 2020). It could be an additional form of central bank moneyA liability of a central bank, including banknotes in circulation and banks’ deposits with the central bank. More alongside cashMoney in physical form such as banknotes and coins. More and the central bank reserves available to commercial banks.

The development of CBDC has raised many questions within the cash community.

- Will CBDC compete with or complement cash?

- Can CBDC emulate the specific attributes of cash (universality, legal tenderMoney that is legally valid for the payment of debts and must be accepted for that purpose when offered. Each jurisdiction determines what is legal tender, but essentially it is anything which when offered (“tendered”) in payment of a debt extinguishes the debt. There is no obligation on the creditor to accept the tendered payment, but the act of tendering the payment in legal tender discharges the debt. More, resilience…)?

- Is central bank ‘neutrality’ towards cash and paymentA transfer of funds which discharges an obligation on the part of a payer vis-à-vis a payee. More methods sustainable while openly supporting CBDC?

So, where do we stand today in terms of CBDC?

Let’s start with the ancestor of all CBDCs. The Avant card, launched in 1992, was eventually spun off by the Bank of Finland to the commercial banks in 1995. As debit cards were upgraded to smart card technology, Avant became obsolete and less profitable and was shut down. Other CBDCs have been launched and discontinued. One example is the Dinero Electrónico from Ecuador, operated between 2014 and 2018. According to the Atlantic Council CBDC tracker, the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU) decided in 2016 to use member-state Senegal as a testing ground for a potential union-wide digital currency. However, early in development, the central bank withdrew support, and the project failed.

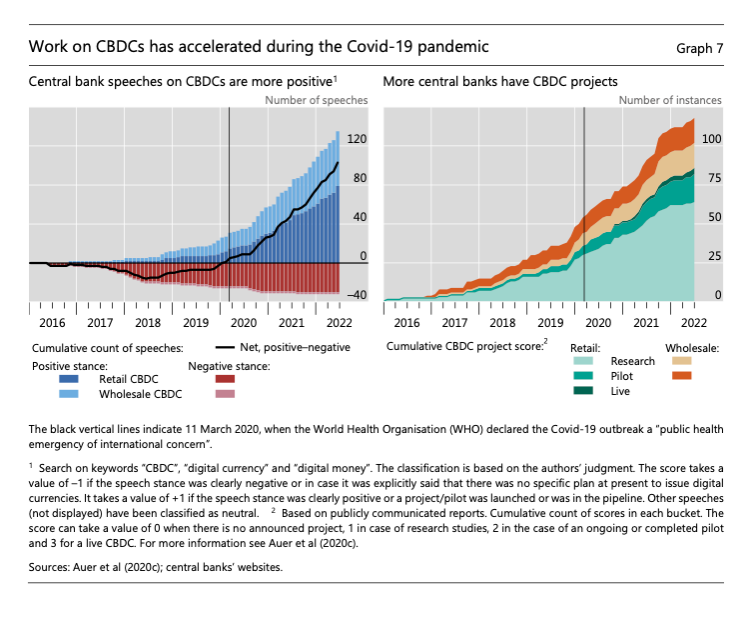

According to the BIS, research and development work on CBDCs kicked into higher gear during the pandemic, with over 60 publicly announced CBDC projects by March 2021 (right-hand panel of the chart below). John Kiff, Managing Director at the CBDC Think Tank, wrote on December 5 that there are now 91 central banks that have recently issued, piloted, experimented with and researched retail CBDC.

Four CBDCs are in activity today. In October 2020, the Central Bank of the Bahamas launched the Sand DollarMonetary unit of the United States of America, and a number of other countries e.g. Australia, Canada and New Zealand. More. In March 2021, the Eastern Caribbean Central Bank (ECCB) announced the public rollout of DCash, and in October, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) launched the e-Naira. The Bank of Jamaica announced JAM-DEX in the first quarter of 2022.

The BIS also measure an unusual but spectacular metric: the positive stance of central banks towards CBDC (left panel of the chart above). This is calculated by classifying speeches mentioning digital currency or moneyFrom the Latin word moneta, nickname that was given by Romans to the goddess Juno because there was a minting workshop next to her temple. Money is any item that is generally accepted as payment for goods and services and repayment of debts, such as taxes, in a particular region, country or socio-economic context. Its onset dates back to the origins of humanity and its physical representation has taken on very varied forms until the appearance of metal coins. The banknote, a typical representati... More as positive or negative. It is striking that until Q1 2021, the positive and negative speeches were relatively balanced. After the announcement of the Covid-19 outbreak, the number of pro-CDBC addresses grew exponentially, whereas the hostile speeches remained stable. At the end of 2022, there are three speeches in favour of CBDC for one against.

Can Central Banks promote CBDC and not cash?

What happened to the central banks’ neutrality towards payment instruments? Most central banks have explained that considering their role as an overseer of the payment systems, they need to retain a neutral stance vis-à-vis different payment methods and cannot promote cash over alternative payment methods. If this is true for cash, why does it not apply to CBDC? Considering that the vast majority of central banks have not (yet) issued a digital currency, it also seems questionable to speak out in favour of a solution which has not been proven or tested.

What about adoption?

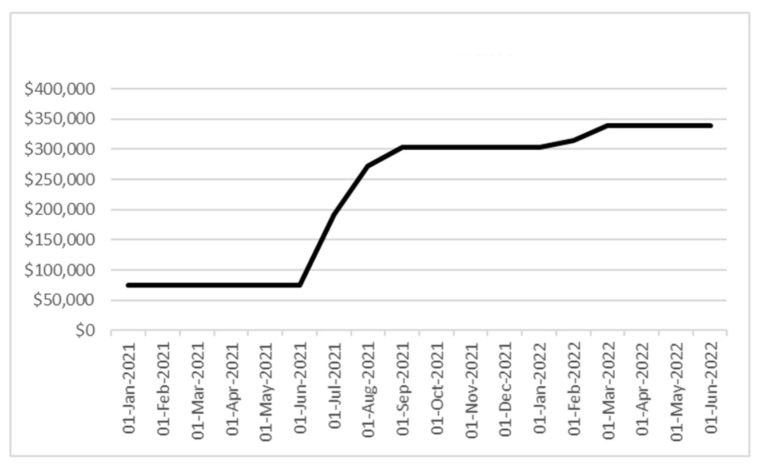

Martin Walker gives a detailed analysis of the use of the Sand dollar launched by the Central Bank of the Bahamas in 2020 and described by PwC as the “world’s most mature CBDC”. A central bank paperSee Banknote paper. More estimates that in July 2022, 32,736 wallets had been created, representing an adoption rate of 7.9%. By June 2022, almost two years after the launch, there were still only $338,908 in circulation. To put that into context, there are over $30m in coins in circulation, plus almost $506m Bahamian-issued banknotes (plus at least as many US dollars). With a population of around 393,000 people, the per capita circulation of sand dollars is about to 86 cents, compared to a per capita circulation of $78 in coins and $1,287 in Bahamian notes.

Sand Dollars in Circulation Source: Central Bank of the Bahamas; Martin Walker

As for the e-naira launched in October 2021 by the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), it is used by less than 0.5% of the population, according to Bloomberg, which estimates, in comparison, that over 33 million Nigerians have owned or traded cryptocurrencies. The CBN is now capping cash withdrawals a year after the launch to encourage more robust usage of the digital naira.

From January 9, over-the-counter cash withdrawals will be limited to ₦100,000 ($225) per week for individuals and ₦500,000 ($1,123) for businesses. Taking cash out of ATMs will be capped at ₦20,000 ($45) daily, with only ₦200 ($0.45) notes and smaller denominations available from the machines. Customers will still be able to take out more considerable sums in some instances but will have to pay processing fees of between 5% and 10%. The move was justified as being in line with “the Cashless policy of the CBN.”

The pandemic has clearly shown how access to cash reduces uncertainty during a crisis and can be interpreted as an exceptional public insurance service. As the global economy is facing heightened uncertainty due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, geopolitical tensions, and extreme weather events due to global warming, a well-functioning cash infrastructure remains necessary for the foreseeable future.