Cash and Crises: No Surprises by the Virus

Global CashMoney in physical form such as banknotes and coins. More Demand has Increased Steeply over the past 30 Years

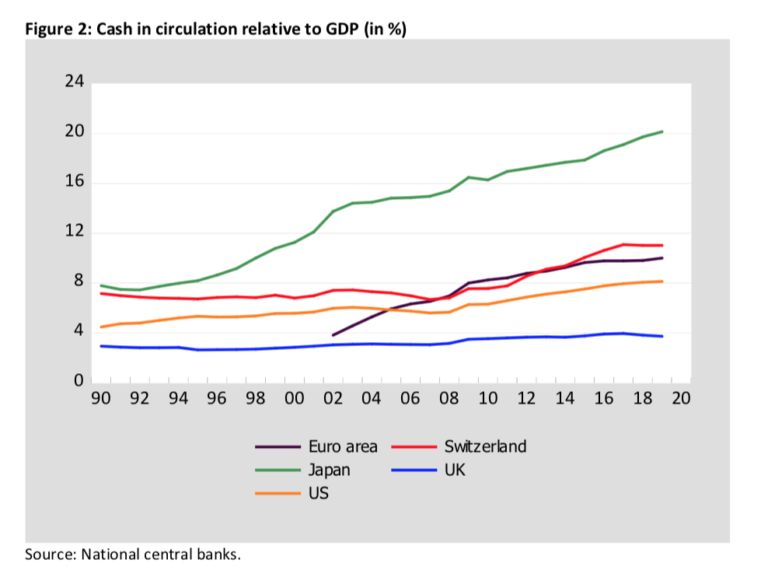

Over the past years, there has been an intense discussion about restricting the use of or even abolishing cash (Rogoff, 2016, Summers, Sands, 2016). The advocates of such drastic measures typically refer to the fact that cash will become obsolete anyway as electronic payments gain more and more importance. However, global cash in circulationThe value (or number of units) of the banknotes and coins in circulation within an economy. Cash in circulation is included in the M1 monetary aggregate and comprises only the banknotes and coins in circulation outside the Monetary Financial Institutions (MFI), as stated in the consolidated balance sheet of the MFIs, which means that the cash issued and held by the MFIs has been subtracted (“cash reserves”). Cash in circulation does not include the balance of the central bank’s own banknot... More increased enormously since the beginning of the 1990s (see Fig 1, and its trend growth became even steeper over time (Jobst & Stix, 2017; Bech et al., 2018; Shirai & Sugandi, 2019; Ashworth & Goodhart, 2020). For the major currencies, growth in cash holdings even exceeded GDP growth in the last decades (See Fig 2.)

Crises Stimulate Demand for Cash

At the current juncture, the Covid-19 pandemic led to an exceptionally strong increase of cash demand all around the world despite efforts from the retail sector, FINTECH, and the card industry to convince consumers to use electronic payments more intensively (Beretta & Neuberger, 2020). And, indeed, in many countries, cashless payments were more frequently used at the point of sale (Ardizzi et al., 2020, Caswell et al., 2020). Consequently, other motives of holding cash must have overcompensated this decrease in cash transaction balances.

The paperSee Banknote paper. More by Rösl & Seitz (2021) intends to provide a deeper insight into the crisis-related motives of cash demand, not only in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic but in times of crises more generally. In addition, it also provides evidence of a trend shift over time towards non-transactional demand for cash. The authors present descriptive, graphical, and econometric evidence in an international context with an emphasis on the most important currencies worldwide (US-dollar, EuroThe name of the European single currency adopted by the European Council at the meeting held in Madrid on 15-16 December 1995. See ECU. More, Swiss Franc, Japanese Yen, Pound SterlingPound sterling, British currency. More) and advanced economies. They distinguish between small and large denominations. The situation in selected less developed countries (e. g., Egypt, Brazil) and in those where cashless payments are widespread (e. g., Sweden) is also taken into consideration, albeit to a less thorough extent.

Despite the increasing use of electronic payments worldwide, the notion that cash loses importance can be clearly refuted. The observed increase in global cash in circulation over the past 30 years cannot be attributed to cash issues of developing countries that might overcompensate a supposed reduction in cash demand in more technologically advanced economies. To the contrary, the overall development was strongly driven by the traditional “hard currency” central banks in an environment of declining interest and inflation rates. And especially in times of severe crises, an additional stimulus to cash arose. This is also true for Scandinavian countries.

Hereby, it does obviously not matter what kind of crisis occurs. MoneyFrom the Latin word moneta, nickname that was given by Romans to the goddess Juno because there was a minting workshop next to her temple. Money is any item that is generally accepted as payment for goods and services and repayment of debts, such as taxes, in a particular region, country or socio-economic context. Its onset dates back to the origins of humanity and its physical representation has taken on very varied forms until the appearance of metal coins. The banknote, a typical representati... More holders tend to demand more cash in technological crises such as Y2K as well as during times of doubts about the stability of the financial system (2008/9). In addition, the same is true for natural disasters like hurricanes and the current Covid-19 crisis. With respect to the motives behind the increase in global cash demand, we observe a shift from transaction balances towards more hoardingThe term refers to the use of cash as a store of value. However, the term has a negative connotation of concealment, and is often used in the context of the war on cash. See Precautionary Holdings. More or store-of-value motives, especially in the form of large denominationEach individual value in a series of banknotes or coins. More banknotes.

Cash reduces Uncertainty in Times of Crisis

However, up to now, the crisis-related increase in the demand for cash did not changeThis is the action by which certain banknotes and/or coins are exchanged for the same amount in banknotes/coins of a different face value, or unit value. See Exchange. More the trend in cash in circulation. It remains to be seen whether this is also true for the current Covid-19 crisis. First analyses reveal that at least paymentA transfer of funds which discharges an obligation on the part of a payer vis-à-vis a payee. More patterns might have changed permanently (Alfonso et al., 2021; Ardizzi et al., 2020; Jonker et al., 2020). In normal times, some emphasize the alleged inefficiency, inconvenience, and costly provision of cash. Against the background of the results of Rösl & Seitz (2021), however, cash seems to play an important part in successful crisis management.

The sheer possibility of having access to cash reduces uncertainty during a crisis and can be interpreted as a special kind of public insurance service. Of course, such an insurance provided by the central banks generates moral hazard. Nevertheless, one should have a critical view on suggestions and political actions that aim at restricting the use of cash and making cash unattractive. Once payments in cash reach a critical lower level, it becomes unattractive for retailers to accept and for banks to supply cash and to offer the possibility to deposit banknotes and coins. An alarming example in this direction is Sweden, which came in the past years already quite close to this lower threshold. The latest actions of official authorities to reverseThe back of the banknote or coin. See Obverse. More this trend speaks for themselves (Ingves, 2020).

This post is also available in:

![]()