Cash and Disability

“The accident which deprived my mother of her career and her mobility means that she can no longer care for her disabled husband, cook a meal or babysit for her grandchildren. […] Each time her card is refused, it’s a reminder of the independence she has lost and the powerlessness of disability.” – Anna Timms, The Guardian

Writing for CashEssentials has made me aware that means of paymentA transfer of funds which discharges an obligation on the part of a payer vis-à-vis a payee. More are not equally accessible. When I returned from New York City to Mexico City during the Covid-19 pandemic, I noticed how my parents and seniors struggled to use payment cards and digital payments. Many find it easier to withdraw cashMoney in physical form such as banknotes and coins. More from ATMs and prefer to use cash in daily transactions.

Once, when using a debit card, my dad entered the wrong PIN three times. The bank froze his card, and he lost access to the funds for weeks. My mom’s visual capacity has diminished: the chances that she will make mistakes when paying with cards are higher than with banknotes and coins. Both get frustrated with banks’ digital customer service channels. They find banking apps challenging and confusing to navigate menus and options by telephone banking.

This happens across countries. In 2022, a Spanish retiree, Carlos San Juan de la Orden, started a ChangeThis is the action by which certain banknotes and/or coins are exchanged for the same amount in banknotes/coins of a different face value, or unit value. See Exchange. More.org campaign that showed how banking’s rampant digitalization increased senior adults’ financial exclusion. The petition reached close to 650,000 signatures.

Digital Payments for Seniors and Disabled People

“53% of 14.3 million adults in the Netherlands cannot perform all payment services independently [including] people with a mild intellectual disability, people with a walking impairment, people who have such poor mobility that they use a scooter or wheelchair, people with limited hand function, people who are hearing-impaired, people who are severely hearing-impaired or deaf, people who are visually impaired, people who are visually impaired or blind, people aged 65 to 74, and people aged 75 and over” (Broekhoff et al. 2023: 5).

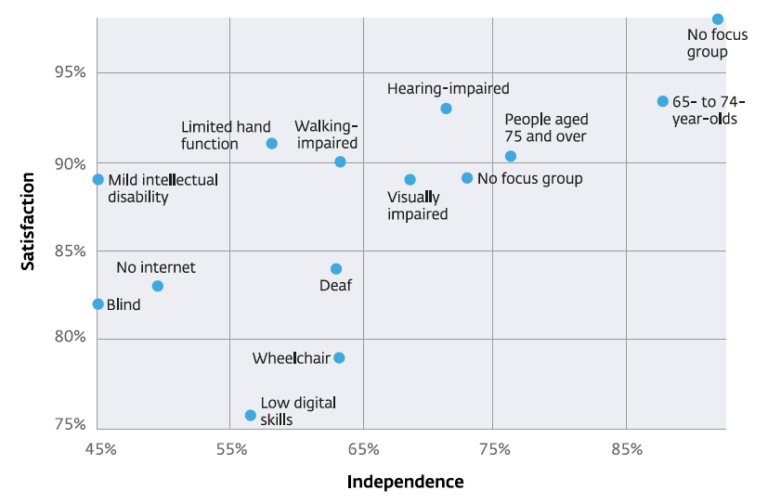

In a recent paperSee Banknote paper. More, researchers from De Nederlandsche Bank (DNB) explored the obstacles that at-risk groups face when using digital payments. While most people are satisfied with how they can pay, people with low digital skills and wheelchair users are the least satisfied (see Graph 1). The satisfaction of focus groups correlated positively with the independence to perform payment services.

Graph 1. Netherlands: Independence and Satisfaction of Various Groups of People Regarding Payment Services

Source: Broekhoff et al. (2023: 33).

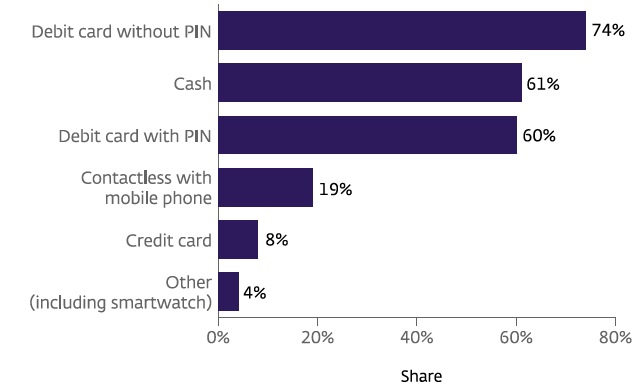

Most interviewees paid using debit cards, preferably without PINs (see Graph 2). Cash was their second most used payment methodSee Payment instrument. More.

Graph 2. Netherlands: Use of Payment Methods in Retail Payments

Source: Broekhoff et al. (2023: 42).

In-depth interviews found that:

- People with physical disabilities have difficulty locating and operating ATMs, payment terminals, and mobile phones.

- Blind and visually impaired people struggle to read text on screens, keyboards in ATMs and payment terminals, webpages, and banking apps.

- People with mild intellectual disabilities tend to be financially vulnerable, and most need help with their banking.

- Seniors struggle with digital banking and use digital payments less than adults.

- Empty ATMs and ATMs with high-denomination (€50) banknotes pose issues to people with mild intellectual disabilities, who tend to be financially vulnerable.

In their conclusions, the researchers issued four recommendations for retailers, banks, ATMs, and payment equipment operators (Broekhoff et al. 2023: 5),

- Preserve and improve the non-digital payment world.

- Raise awareness of accessibility initiatives and launch new initiatives.

- Make better use of technology to increase accessibility.

- Tailor digital solutions to users.

Payment Instruments Are Not Neutral

The digital payments infrastructure is ill-prepared to accommodate the needs of seniors and disabled people. Cash restores and provides agency to disabled and older people. Chart 1 shows how many people find using cash in retail transactions easier than card and digital payments.

Chart 1. Disability and Means of Payment

While I can only talk with first-hand experience regarding neurodiversity as an adult with ADHD, I would encourage readers to provide feedback, mainly as this think tank explores the role of cash as a basic right.