Moving and Living Abroad: Cash and Payments

A Ph.D. Student and Candidate in New York City

I lived in New York City from August 2011 to December 2020 to study a Ph.D. in U.S. history at Columbia University and work as a consultant. In 2011, the Obama administration struggled to contain the lingering effects of the 2008 financial crisis and the Great Recession. Shortly after I arrived, Occupy Wall Street protests took over downtown Manhattan.

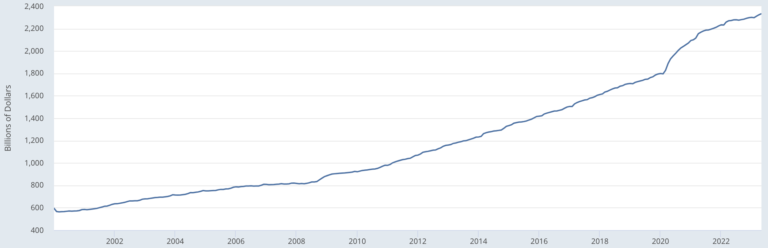

Graph 1. United States: Cash in CirculationThe value (or number of units) of the banknotes and coins in circulation within an economy. Cash in circulation is included in the M1 monetary aggregate and comprises only the banknotes and coins in circulation outside the Monetary Financial Institutions (MFI), as stated in the consolidated balance sheet of the MFIs, which means that the cash issued and held by the MFIs has been subtracted (“cash reserves”). Cash in circulation does not include the balance of the central bank’s own banknot... More, January 2000-May 2023 (billions of U.S. dollars).

Source: FRED, Federal Reserve BankSee Central bank. More of St. Louis (2023).

While I received a stipend and had some savings, New York’s cost of living often made it challenging to balance my budget. Within three months of opening a bank account, Citi offered me a credit card. Credit card spending became a lifeline, but eventually, I had to allocate a significant portion of my income to pay down my balances.

CashMoney in physical form such as banknotes and coins. More made it easier to budget then. I was able to find an ATM to withdraw cash easily. I lived a block from a TD Bank branch in Sunset Park, a working-class immigrant neighborhood in South Brooklyn. Most bodegas in New York City had ATMs that, while charging a commission, made it easy to get cash when needed. Cash payments prevailed in most of Lower Manhattan after Hurricane Sandy caused widespread outages in 2012.

I downloaded Venmo in December 2015 and started using it shortly after. Venmo made dividing restaurant bills much easier among my friends. Many retailers adopted new tablet-based registries at the time, such as the Square terminal, and some even went cashless.

New York became the global capital of the Covid-19 pandemic in March 2020. Amid the grim contagion, hospitalization, death rates, and the dysfunction of the Trump administration, I distinctly remember the refrigerated trucks parked next to the many funeral houses in my neighborhood. Then, the killing of George Floyd in May 2020 galvanized people to action. A Minneapolis police officer murdered him after Floyd, a Black American, attempted to pay for goods at a grocery store with a counterfeitThe reproduction or alteration of a document or security element with the intent to deceive the public. A counterfeit banknote looks authentic and has been manufactured or altered fraudulently. In most countries, currency counterfeiting is a criminal offence under the criminal code. More USD20 bill. I participated in several protests and observed the rapid deterioration of U.S. democracy during Trump’s campaign to retain the presidency.

Cardless payments were the norm in the Covid-19 pandemic. Then, retailers enabled their paymentA transfer of funds which discharges an obligation on the part of a payer vis-à-vis a payee. More terminals to accept them, and the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) started changing the subway’s turnstiles, allowing the riders to use contactless payments.

However, most people in Sunset Park (Mexicans, Chinese migrants, Dominicans, and other Latin American residents) paid using cash. Undocumented workers cannot open bank accounts on account of U.S. migration restrictions. That meant several friends could not claim any Covid-19 relief programs enacted during 2020 and 2021. They still cash their paychecks at expensive check-cashing dealers.

Hola, But Not Quite for Long: Moving Home to Mexico

I moved from New York City to Mexico City in December 2020, before vaccines were available for distribution. Then, I learned that using mobile banking and payment apps becomes extremely difficult when moving abroad. When I switched my country from the United States to Mexico in the Apple App Store, I could no longer update my U.S. banking and payment apps and had to get a second phone to use them.

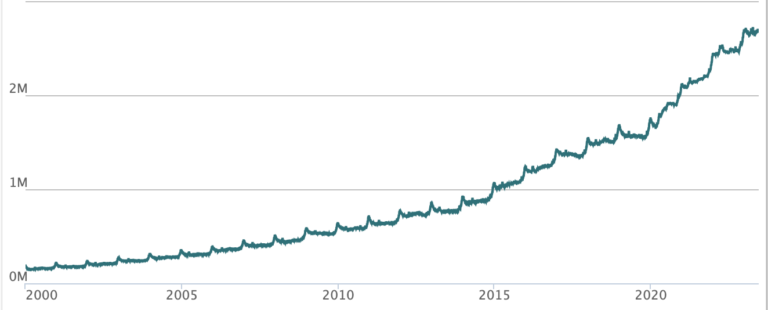

Graph 2. Mexico: Cash in Circulation, January 2000-June 2023 (trillions of Mexican pesos).

Source: SIE, Banco de México: Base monetaria, circulante y depósitos (2023).

While digital payments in Mexico City prevail more than in the rest of the country, cash use is ubiquitous, and there are plenty of ATMs in the city. For the two years I spent in my hometown, I paid most of my expenses with BBVA and American Express Aeromexico Rewards credit cards (due to mileage rewards and cash-back programs) but always withdrew cash from my BBVA account for small-value transactions.

While many retailers, restaurants, and bars adopted payment terminals during the pandemic, street vendors still use cash as their primary payment instrumentDevice, tool, procedure or system used to make a transaction or settle a debt. More. Fintech solutions and payment apps have increased in the last few years. However, I might have used CoDi (the central bank’s QR payment solution) less than five times in two years.

Cash can be convenient for me. But my parents’ generation uses cash conspicuously. My grandparents did not have bank accounts. Their financial exclusion ended in their late years as several governments enacted programs to distribute social benefits employing debit cards and current accounts. But that did not make them any more financially included. They relied on cash on hand. Mexico’s high uncertainty makes people nervous about going out without little or no cash.

When I returned, I employed Uber and Didi to travel across Mexico City and always paid with my credit card on file. Most cabs in the capital only accept cash to pay their fare. However, both transportation mobility platforms were unavailable one day, and I hopped in a taxi. I spent much less that night going to my destination.

Cashing In on Unused Balances (and Registered Payment Card Numbers)

Interestingly, several events I attended shifted to cashless, from art exhibits (Salón Acme, February 2022) to music festivals and concerts (Dua Lipa, September 2022). Organizers asked people to charge balances to wrist devices and use them to make payments. All prices are set to prevent rounding, and attendees either forget or face a belated process to claim their unused balances.

The day I traveled to London Heathrow via Aeroméxico, I attempted to pay for an extra suitcase via the airline’s website. The portal crashed, and the payment did not show up when I checked in at the airport. I decided to carry my third suitcase on board. An hour before I boarded the flight, I got an app notification: Aeroméxico had just processed the payment. It took two and a half months for the airline to reimburse their mistaken charge.

Shortly after arriving in Heathrow, I received a notification from my BBVA banking app: Ecobici, Mexico City’s bike share system, had charged me for a full-year subscription. Last year, the city government ceded control over Ecobici to a consortium that includes the U.S. mobility company Lyft. The new Ecobici requires users to registerSee See-through register. More with a debit or credit card, burying deep in their pages-long terms of service that they will renew the subscription unless users cancel it not from their mobile app but through Ecobici’s website.

Despite my complaints about being unable to use the bikes from abroad, the Ecobici customer service representative denied my request for a refund. The experience is emblematic of how the Mobility Secretariat of Mexico City (Semovi) has sought to promote digital payments and disincentivize the use of cash in its services. Despite the high levels of financial exclusion, Semovi has yet to realize this biased policy reduces access to clean transportation in highly-polluted Mexico City.

These incidents were the prelude to countless frictions with banking and digital payments in the United Kingdom, the second country I have moved to in three years. Digital payments might be convenient at first sight, but they are not. Cash has been my most reliable means of payment in these three distinct countries.