The Regressive Nature of Card Payments

Since the 1990s, some scholars have argued that lower-cost debit card and cashMoney in physical form such as banknotes and coins. More transactions subsidize credit card payments (see Frankel 1998).

- Merchants do not typically surcharge and apply uniform pricing, regardless of the payment instrumentDevice, tool, procedure or system used to make a transaction or settle a debt. More.

- All consumers pay the same amount, but credit card users can get a price discount after a transaction through cash back, merchandise, card rewards, miles, or hotel rooms.

- Card payments have regressive distributional effects, as credit cardholders tend to be higher-income consumers, subsidized by lower- and middle-income consumers.

- Card schemes have actively lobbied against surcharging to fund their reward systems and incentivize consumers to favor their products.

Evidence from Canada (1)

In a 2017 paperSee Banknote paper. More, Anneke Kosse, Heng Chen, Marie-Hélène Felt, Valéry Dongmo Jiongo, Kerry Nield, and Angelika Welte (Bank of Canada, BoC) used survey data from retailers, financial entities, and cash management companiesCompanies specialized in the logistical handling of cash including several of the following operations: transportation, storage, counting and processing, packaging, replenishment and servicing of ATMs. See Cash-in-Transit. More to look into the costs of cash, debit and credit card payments in Canada in 2014.

- The cost of cashAlthough banknotes are delivered to the citizens free of charge and their use does not involve a specific fee, costs are generated during their manufacturing, storage and circulation process, which are covered by different social agents (central banks, commercial banks, retailers etc). More and card payments at point-of-sales (POSAbbreviation for “point of sale”. See Point-of-Sale terminal. More) in Canada amounted to CAD15.3 billion, or 0.78% of GDP (Kosse et al. 2017: 17).

- Regarding total resource costs, debit cards were the least costly, followed by credit cards, and cash was the costliest paymentA transfer of funds which discharges an obligation on the part of a payer vis-à-vis a payee. More instrument. Debit cards were the least expensive regarding resource costs per volume and value; credit cards are the most expensive per value, and cash is the most costly per volume (Kosse et al. 2017: 20).

- Regarding variable costs, cash is the cheapest for transactions up to CAD6, and debit cards are the least costly for transactions larger than CAD6 (Kosse et al. 2017: 20-21).

- Based on private costs alone, consumers would prefer to use credit cards. In contrast, retailers and financial entities would choose debit card payments (Kosse et al. 2017: 23-24).

Evidence from Canada (2)

In a 2019 paper, Kim P. Huynh, Gradon Nicholls, and Oleksandr Shcherbakov (BoC) used consumer-side and merchant-side surveys to determine the cost of payments for different consumers.

- Consumers almost always (99.8%) had a payment card of some kind, with 83% owning both a debit and a credit card; 22% of merchants only take cash, and 70% accepted both debit and credit cards. Cash was the most common payment methodSee Payment instrument. More (44%), followed by credit and debit cards, with 33% and 23%, respectively (Huynh et al. 2019: 3-4).

- Based on a counterfactual analysis, the researchers found that “an average consumer spends about CAD11 a month to have cash and debit in her wallet, relative to holding only cash. Consumers who adopt all means of payment instead receive a relative benefit of about CAD48 a month.” (Huynh et al. 2019: 13).

- Thus, consumers using cash, credit, and debit cards would benefit most; those using cash only would be the least affected, while people using cash and debit cards would experience the most considerable cost of payments (see Graph 1).

Graph 1. Canada: Variable Private Costs per Transaction By Transaction Value (Canadian Dollars, CAD), 2014

Evidence from the United States and Canada

In a 2020 paper, Marie-Hélène Felt (BoC), Fumiko Hayashi (Federal Reserve BankSee Central bank. More of Kansas City), Joanna Stavins (Federal Reserve Bank of Boston), and Angelika Welte (BoC) quantified consumers’ net pecuniary cost of using cash, credit and debit cards in the United States and Canada.

- Many low-income consumers do not own credit cards because they have no credit history or low credit scores. Less than 50% of U.S. and about 60% of Canadian consumers with annual household incomes below $25,000 report having credit cards (Felt et al. 2020: 3).

- The researchers define consumers’ net cost of using a payment instrument as fees paid to financial entities, rewards from credit or debit card issuers, and the merchants’ pass-through of the cost of accepting payments setting up higher retail prices (Felt et al. 2020: 33).

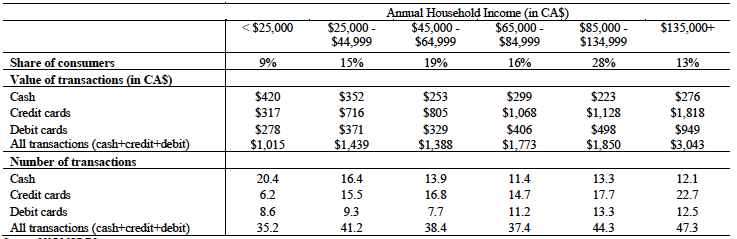

- Low-income consumers in the United States and Canada have the lowest cost of payments in absolute terms, given that their transactions are fewer and smaller in value (see Table 1).

Table 1. Average Value and Number of POS Purchases per Consumer per Month by Payment Instrument and Income Cohort.

Panel A: United States (2018)

Source: Felt et al. (2020: 38, 39).

- However, low-income customers face the highest cost of payments relative to their transaction amount compared to high-income consumers (see Graph 2, Felt et al. 2020: 4-5, 21, 49). The ratio of the net cost to POS purchase amount is the highest for the lowest-income cohort in the United States (1.41%) and Canada (1.88%); it is the lowest for the highest-income cohort in the United States (0.82%) and Canada (1.35%).

- The ratio of merchant cost to POS purchase increases proportionally with income in the United States.

- This ratio increases and decreases with income in Canada, as higher-income Canadians substitute cash with debit cards, the least costly payment method for Canadian merchants (see above, Kosse et al. 2017: 20).

Graph 2. Ratio of Net Pecuniary Cost to POS Purchase Amount in the United States (2018) and Canada (2017)

Source: Felt et al. (2020: 49).

Poverty Premium When Using Cash Only

There is a “poverty premium” when using cash only when retailers accept cards widely.

- “The reality is, if you can’t shop online you will pay more using cash because you can’t get online deals or direct debits where you often get a discount, you can’t shop around or buy in bulk,” said Natalie Ceeney, chair of the Cash Action Group.

- Relying only on cash “can expose [survivors] to predatory and expensive service like check cashing. It also serves as a barrier to safety – renting a car or paying for a hotel room is difficult, if not impossible, with cash,” said a FreeFrom report on cash grants to intimate partner violence survivors (2021: 20).