Dutch Central Bank says Cash must remain Accessible and Available

Transactional CashMoney in physical form such as banknotes and coins. More Usage is Falling

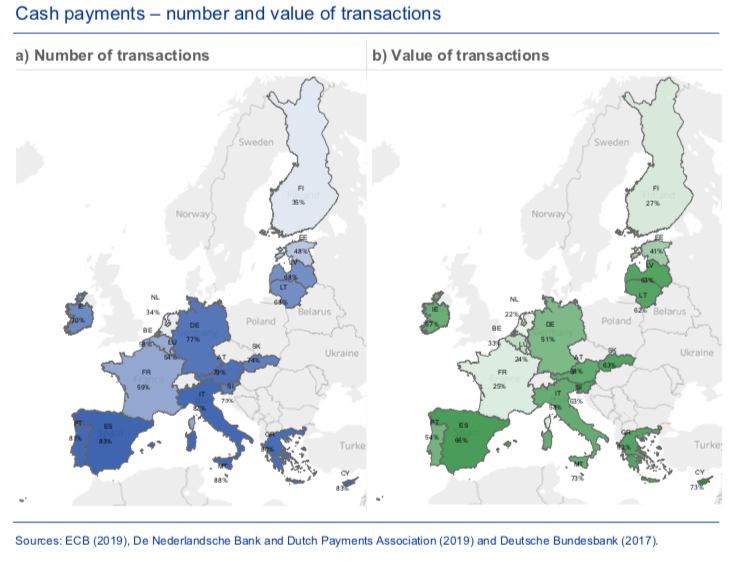

According to the recent ECB Study on the Payment Attitudes of Consumers in the Euro Area (SPACE) , the Netherlands – along with Finland and Estonia – are amongst the euro-area countries with the lowest levels of cash transactions. In 2019, 34% of point-of-sale and person-to-person transactions were settled in cash in the Netherlands representing 22% of the value of transactions compared to a euro-area averages of respectively 73% and 48%. The figure has dropped to just over 20% at the end of October 2020, due to changing consumption and paymentA transfer of funds which discharges an obligation on the part of a payer vis-à-vis a payee. More behaviour since the pandemic. The DNB expects these changes to be permanent.

The DNB report stresses that the sharp decline in the use of cash is increasing pressure on the availability and acceptance of cash and is shrinking the cash infrastructure

ATM numbers should not fall further

In terms of access to cash, the Netherlands have seen a sharp and continued drop in the number of ATMs. The number of ATMs peaked in 2008 at 8,654 units and has since declined by 42% to 4,968 units in 2019. The pooling of the networks of the leading banks under a single utility-type entity, Geldmaat, has not slowed down the trend. Furthermore, a spate of explosive attacks on ATMs has led banks to take further measures to restrict access including closing ATMs at night or temporarily shutting them down. In co-operation with supply-chain partners Brink’s and Geldmaat, the DNB has modelled the minimum number of ATMs required to ensure a back-up role in the event of an outage of digital payment systems; the number of ATMs should not fall further for the model to work.

A Shrinking ATM Network

Broadening the Acceptance of Cash

The acceptance of cash by merchants and public institutions has also declined. In spite of its legal tenderMoney that is legally valid for the payment of debts and must be accepted for that purpose when offered. Each jurisdiction determines what is legal tender, but essentially it is anything which when offered (“tendered”) in payment of a debt extinguishes the debt. There is no obligation on the creditor to accept the tendered payment, but the act of tendering the payment in legal tender discharges the debt. More status, merchants are allowed in the Netherlands to refuse cash payments even though this is in contradiction with European Commission Recommendation 2010/191/EU on the scope and effects of legal tender of euroThe name of the European single currency adopted by the European Council at the meeting held in Madrid on 15-16 December 1995. See ECU. More banknotes and coins which states that “The acceptance of euro banknotes and coins as means of payments in retail transactions should be the rule.” The DNB monitors closely the degree of cash acceptance and a recent survey has shown that 96% of retailers accept cash in 2020, down from 97% in 2019; however, 35% of retailers actively encourage customers to pay elecronically. The downward trend in cash acceptance is forcing citizens to pay with non-cash instruments. However, both the Parliament and the Government have spoken out in favour of broader acceptance of cash.

Cash plays an Essential Role in Society

The DNB emphasizes – again – the specific attributes of cash: it is the only from of public moneyFrom the Latin word moneta, nickname that was given by Romans to the goddess Juno because there was a minting workshop next to her temple. Money is any item that is generally accepted as payment for goods and services and repayment of debts, such as taxes, in a particular region, country or socio-economic context. Its onset dates back to the origins of humanity and its physical representation has taken on very varied forms until the appearance of metal coins. The banknote, a typical representati... More available to the public; it is the basis of trust in the monetary system ; it is a back-up solution in the event of the failure of electronic payments; it is ‘generally’ – but not universally – accepted; it is an important budget management tool; it enables transactions without third-party intermediation. The DNB concludes there is a social need for cash but that declining usage is jeopardizing the existing infrastructure.

Shaping the Cash CycleRepresents the various stages of the lifecycle of cash, from issuance by the central bank, circulation in the economy, to destruction by the central bank. More of the Future

This raises the question of how to develop a sustainable, efficient and resilient cash cycle. Should the cash cycle be left entirely to market forces or should the central bank increase its involvement? Are voluntary agreements sufficient, or is more regulation required? Is the current distribution of responsibilities between cash cycle stakeholders optimal, or do we need to make adjustments? Which parties should bear which costs? DNB will commission a study on the cash infrastructure for the medium term based on these questions.

This post is also available in:

![]()