The Use of Cash in U.S. Payments during the Covid-19 Pandemic

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, the share of cashMoney in physical form such as banknotes and coins. More in the United States declined from 31% of all payments in 2016 to 26% in 2019, according to findings from the 2019 Diary of Consumer PaymentA transfer of funds which discharges an obligation on the part of a payer vis-à-vis a payee. More Choice of the Federal Reserve. In 2019, debit cards were used more frequently than cash, with a share of 30% of all payments. The growth rate of non-cash payments by number had been accelerating, from 5.1% per year in the 2012-2015 period to 6.7% in the 2015-2018 period, according to findings from the 2019 Federal Reserve Payments Study. According to the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, 13,432 bank branches closed in the United States between 2008 and 2020 (over 14% of all branches).

However, cash has long remained dominant for low-value payments, being used in 47% of payments under US$10 and 33% of payments between US$10 and lower than US$25 (Kim, Kumar, O’Brien 2020a: 6). In 2019, a U.S. consumer carried US$60 on average; the average value of a cash payment (for service and utility bills such as rent, electricity, water, cable television, etc.) was US$27, and the average cash purchase of goods (and gifts and allowances) was US$23 (Greene, Stavins 2020: 11).

The U.S. Public Trusts and Uses Cash in Hard (and Covid-19) Times

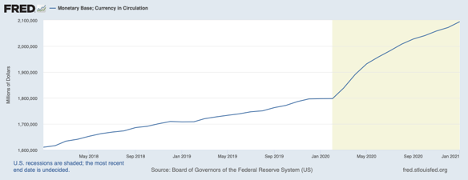

According to the Federal Reserve Economic Data service of the Federal Reserve BankSee Central bank. More of St. Louis, currencyThe money used in a particular country at a particular time, like dollar, yen, euro, etc., consisting of banknotes and coins, that does not require endorsement as a medium of exchange. More in circulation in the United States peaked in January 2021, at US$2.09 trillion. In 2020, cash in circulationThe value (or number of units) of the banknotes and coins in circulation within an economy. Cash in circulation is included in the M1 monetary aggregate and comprises only the banknotes and coins in circulation outside the Monetary Financial Institutions (MFI), as stated in the consolidated balance sheet of the MFIs, which means that the cash issued and held by the MFIs has been subtracted (“cash reserves”). Cash in circulation does not include the balance of the central bank’s own banknot... More grew by US$297 billion, an annual growth rate of 16.5% (see Graph 1 below). The acceleration took place in March and April 2020.

After the Covid-19 pandemic, U.S. consumers reported holding more cash during lockdowns, mainly out of uncertainty and precaution. At the beginning of the pandemic (April 2020), both consumers who usually carry and those who do not generally have coins and notes reported holding on to extra cash in their wallets and storing additional cash reserves in their homes or offices due to the pandemic (Kim, Kumar, O’Brien 2020b: 2-3).

U.S. consumers have not been scared by sensational and alarmist news about cash as a vector of Covid-19 transmission. At least 57% of respondents to a May 2020 survey commissioned by the Federal Reserve System Cash Product Office reported using cash in at least one transaction (Kim, Kumar, O’Brien 2020b: 4). Most consumers (70%) said they were not avoiding cash as a means of payment, out of concerns about coins and notes as a vector of transmission (Kim, Kumar, O’Brien 2020b: 5).

The Exclusionary Nature of Cashless Solutions

Tellingly, “[t]he Federal Reserve has not taken any additional procedures with regard to the handling of cash than it had for any other operations that were in the building,” according to David Lott, payment risk expert in the Retail Payments Risk Forum at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. However, 7% of cash users surveyed reported that retailers refused to accept cash in payments (Kim, Kumar, O’Brien 2020b: 4). The problem has exacerbated as the pandemic continued: by August 2020, 45% of users reported that a merchant had requested that patrons use cards at least some of the time, and 24% reporting requests most of the time or always (Coyle, Kim, O’Brien 2021: 6).

The bias against using cash in retail payments “has a repercussion of discriminating against people that don’t have credit. […] To say they don’t want to take cash because of the virus, that’s an incorrect approach to take and the evidence doesn’t support that” as the surface transmission of Covid-19 is “negligible” according to Dr. Neal Goldstein, an assistant research professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at Drexel University. The only medical reason for preferring contactless payments would be to “limit contact between individuals, and it’s easier to maintain six feet of distance,” according to Dr. Utibe Essien, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh.

The consequences of refusing to accept cash in retail payments in regular times are never negligible considering social inequalities in the access to financial products and services, the exclusion of cash users from goods and services, and the fees paid by retailers to card companies such as Visa, Mastercard, Discover and American Express (Wang 2019: 6-7). In 2019, 6% of U.S. adults were unbanked, meaning they did not have a checking, savings, or moneyFrom the Latin word moneta, nickname that was given by Romans to the goddess Juno because there was a minting workshop next to her temple. Money is any item that is generally accepted as payment for goods and services and repayment of debts, such as taxes, in a particular region, country or socio-economic context. Its onset dates back to the origins of humanity and its physical representation has taken on very varied forms until the appearance of metal coins. The banknote, a typical representati... More market account at all, and 16% of U.S. adults were underbanked, meaning they had a bank account but also used alternative financial service products such as money orders, check cashing services, pawnshop loans, auto title loans, payday loans, paycheck advances, or tax refund advances (Division of Consumer and Community Affairs of the Federal Reserve Board 2020: 27).

Financial InclusionA process by which individuals and businesses can access appropriate, affordable, and timely financial products and services. These include banking, loan, equity, and insurance products. While it is recognised that not all individuals need or want financial services, the goal of financial inclusion is to remove all barriers, both supply side and demand side. Supply side barriers stem from financial institutions themselves. They often indicate poor financial infrastructure, and include lack of ne... More Requires Protecting Cash and its Users

The unbanked and the underbanked are more likely to be low-income earners, retirees, immigrants, less educated, people with disabilities, or members of a racial or ethnic minority group: 14% of Black adults and 12% of Hispanic/Latino adults were unbanked, compared to 6% of all U.S. adults (Division of Consumer and Community Affairs of the Federal Reserve Board 2020: 27). That is to say, “[t]here is a significant correlation between the use of cash, prepaid, debit, high-end credit and wealth, and there’s a huge correlation between wealth and race. […] Our payment system is geared toward helping the wealthy and charging the poor,” according to Aaron Klein, senior fellow in economic studies at the Brookings Institution.

Preserving the use of cash is part of a holistic strategy to ensure that all individuals have access to “safeSecure container for storing money and valuables, with high resistance to breaking and entering. More, efficient, and inclusive payments” in pandemic and post-pandemic times (Bostic, Bower, Shy, Wall, Washington 2020: 21). Several U.S. cities, including New York, San Francisco, Berkeley (California), and Philadelphia, have implemented policies to protect cash users in retail payments. In May 2019, Senators Kevin Cramer (Republican of North Dakota), Bob Menendez (Democrat from New Jersey), and Representative Donald M. Payne Jr. (also a Democrat from New Jersey) introduced federal legislation (H.R. 2660, Payment Choice Act) to protect the right to use cash in retail transactions and prevent fully-cashless businesses from disadvantaging cash users. The initiative was strongly endorsed by several consumer rights and financial empowerment groups as well as racial justice organisations.