A Global Update on Cash Demand in Turbulent Times: Part I

CurrencyThe money used in a particular country at a particular time, like dollar, yen, euro, etc., consisting of banknotes and coins, that does not require endorsement as a medium of exchange. More News has published annual updates on banknoteA banknote (or ‘bill’ as it is often referred to in the US) is a type of negotiable promissory note, issued by a bank or other licensed authority, payable to the bearer on demand. More developments at the global level since September 2017. Because of the exceptional situation created by the Covid-19 pandemic, mirrored in the decreasing transactional and increasing precautionary demand for cashMoney in physical form such as banknotes and coins. More, the update was published last year in two parts. The first part focused on developing banknote circulation in value terms in 2020, comparing it with the past. The second part, when more information was available also on the denominational demand, shed further light on the store-of-value function of cash during the pandemic.

The hope that this year’s update would illustrate some kind of return to a new normal in cash demand has shown to be unrealistic. Not only have the lockdowns during the pandemic disrupted global supply chains, but the shocking Russian invasion of Ukraine has recently created further uncertainty. Even if the war has hit hardest on the Ukrainian people and infrastructure, its impacts have been felt worldwide; besides creating a strong reaction, it has brought about galloping inflation of food and energy prices.

All this means that this annual update also illuminates the more recent events; it will be again this year divided into two parts. The current first part will consider the development of banknote circulation in value terms in 2021 and address what happened to the higher-than-normal cash balances accumulated during 2020. In addition, the effects of the cash paradox referred to above will be considered shortly. The second part will be published in September when more extensive information is available in volume terms. The impacts on cash demand caused by the growing inflation and the geopolitical tensions created by the Russian attack can be assessed. The second part will further elaborate on the potential consequences of recent developments for the future of cash.

Banknote circulation in value terms in 2021

When addressing banknote demand globally, the most widely publicly available information is the value of banknotes in circulation. Besides “banknotes in circulation,” the only public figure in some cases is “cash in circulationThe value (or number of units) of the banknotes and coins in circulation within an economy. Cash in circulation is included in the M1 monetary aggregate and comprises only the banknotes and coins in circulation outside the Monetary Financial Institutions (MFI), as stated in the consolidated balance sheet of the MFIs, which means that the cash issued and held by the MFIs has been subtracted (“cash reserves”). Cash in circulation does not include the balance of the central bank’s own banknot... More,” i.e., the figure also includes coins, which are generally just a few percentages of the total cash in circulation, or “currency outside banks.” The latter figure excludes the banks´ vaultSafe; strong room. A place reinforced with special security measures where high-value objects and documents are safeguarded. In central banks, banknotes and other objects are safeguarded in vaults. More cash. After central banks introduced negative interest rates, the banks´ vault cash increased exponentially in the case of some currencies. So not including it would give a wrong impression of the changes in the demand for banknotes, particularly when the growing inflation has recently begun to impact the interest rate level. However, only very few central banks have introduced negative interest rates, and these central banks typically publish the banknotes in circulation figures. Therefore, using slightly differing concepts will have only a minor, if any, impact on the results of this study.

Using statistics and various publications available on the central bank websites, slightly varying numbers (between 139 and 143) of currencies have been addressed in the following three charts. The figures refer, in most cases, to the end of the year (in some cases, the financial year is not the calendar year, and the statistics may refer to the end of the financial year). Furthermore, a few central banks haven’t yet updated their statistics with figures referring to the end of 2021; in half a dozen cases, annual growth figures referring to the end of an earlier month in 2021 have been used.

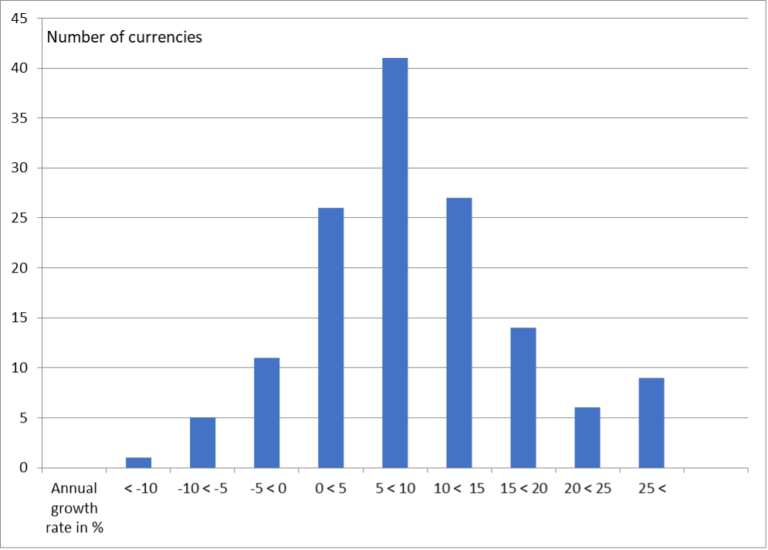

Let us look at the annual growth rates by the value of banknotes in circulation in 2021, as described in Figure 1.

Fig 1: Annual growth rate by the value of banknotes in the circulation of 140 currencies in 2021.

Fig 1: Annual growth rate by the value of banknotes in the circulation of 140 currencies in 2021.

Those readers who have followed earlier global updates will notice that the shape of the distribution of currencies between various brackets of growth rates clearly describes a return towards an average last year. It resembles a normal distribution and is remarkably centered, with more than 70 % of the currencies having an annual growth rate between 0 and 15 percent. There is an unexpectedly small number of outliers at the lower end of the distribution, given the record growth rates in 2020. So, towards the end of 2021, the higher-than-normal cash balances accumulated during the pandemic hadn’t been consumed or abandoned globally. At the higher end of the distribution, the currencies showing growth rates of more than 25 % suffer from high inflation in most cases.

The general impression conveyed by Figure 1 is confirmed by Figure 2, in which the growth rate in 2021 is compared with those in 2020 and 2019, the latter being the last “normal” year before the pandemic.

Fig 2: Annual growth rates by the value of banknotes in circulation in 2019, 2020, and 2021.

Fig 2: Annual growth rates by the value of banknotes in circulation in 2019, 2020, and 2021.

The distributions in 2019 and 2021 are surprisingly similar; that of 2020 instead is squeezed to the right towards the higher growth rates. The exceptionality of 2020 can be further highlighted by considering the median annual growth rates by the value of banknotes in circulation during the last ten years. They are depicted in Figure 3.

Fig 3: Annual growth rates by the value of banknotes in circulation in 2019, 2020, and 2021.

Fig 3: Annual growth rates by the value of banknotes in circulation in 2019, 2020, and 2021.

The median annual growth rate trend has been slightly decreasing with small ups and downs. However, the growth rates have been globally higher than the nominal GDP. The year 2020 makes a striking exception in the development, which is explained by the fact that, in 2020, 42 % of the 142 currencies had their highest annual growth rate of the value of banknotes in circulation during the last ten years. It is remarkable that even after such an exceptional year, the median annual growth rate of the value of banknotes in circulation did not fall close to zero or descend to a negative figure but kept the level it had before the pandemic.

Provisional conclusions

Even if the 2021 figures depicted above refer to a return to normality, the situation has been upset by the recent events. Therefore, it is too early to anticipate what will happen to the banknote demand in 2022 or the medium term. On the one hand, the rapidly climbing interest rates will increase the opportunity cost of holding savings in cash; on the other hand, the uncertainty created by geopolitical tensions will increase the precautionary motive to keep cash balances.

Seemingly independently from the growing precautionary demand for banknotes, the long-term trend of the share of cash in transactions is generally decreasing. This divergence in using cash for payments and saving purposes, respectively, might not be an issue if cash remains the dominant means of paymentA transfer of funds which discharges an obligation on the part of a payer vis-à-vis a payee. More in a particular country or region. However, in a situation where cash is on the way to becoming a marginal payment instrumentDevice, tool, procedure or system used to make a transaction or settle a debt. More, this development raises the question, what does it mean to maintain the cash infrastructure and the role of public cash? The answer to several central banks facing this question seems to be the central bank digital currency (CBDC)A digital payment instrument, denominated in the national unit of account, and a direct liability of the central bank, like banknotes. A general purpose CBDC can be used by the public for day-to-day payments like cash. More.

According to the most recent survey of BIS, nine out of 10 central banks in the survey are exploring CBDCs, and more than half are now developing them or running concrete experiments. Furthermore, more than two-thirds of central banks consider that they will likely or possibly issue a retail CBDC in the short or medium term.

There are other reasons for the central banks to develop CBDCs than just the diminishing role of cash in payments. The development work may be related to improving the existing payment infrastructure, or the technological development of a CBDC is found useful per se in this world of growing threats of cyberattacks.

Even if the technological issues related to CBDCs seem to be solvable, the most critical questions in their successful launch relate to two behavioural questions. Why would citizens start to use digital currencies issued by a central bank if they are satisfied with their current digital payment media issued by the private sector; and what is the business case for the banking sector in case a central bank would like to delegate the intermediation of a CBDC to banks? Considering the uncertainty surrounding these behavioural questions, the central banks would benefit from a Plan B in their forward-looking development work.

The trust in physical cash has been evidenced during the Covid-19 pandemic and in earlier crises (See Gerhard Rösl and Franz Seitz: Cash demand in times of crises). Cash is under one’s control and not dependent upon the working of other systems. It is something tangible, which is an essential characteristic under uncertainty. The strong public opposition against CBDC raised in some central bank surveys can indeed result from the perception and worry of the citizens that it will displace cash (See, e.g., Reserve BankSee Central bank. More of New Zealand, Future of MoneyFrom the Latin word moneta, nickname that was given by Romans to the goddess Juno because there was a minting workshop next to her temple. Money is any item that is generally accepted as payment for goods and services and repayment of debts, such as taxes, in a particular region, country or socio-economic context. Its onset dates back to the origins of humanity and its physical representation has taken on very varied forms until the appearance of metal coins. The banknote, a typical representati... More – Te Moni Anamata: Summary of responses to our 2021 issues papers, April 2022.) There is no other public good currently or in the foreseeable future that has or will provide similar properties, highlighting the role of cash as public infrastructure. Therefore, a well-functioning cash infrastructure is the Plan B for those central banks developing CBDCs because of the diminishing role of physical cash in payments. That does not mean the maintenance of the current infrastructure but also setting innovative solutions needed in the changing environment. This kind of Plan B is a prerequisite for the availability and usability of cash in a crisis. The central banks have, in this respect, very good reasons to advocate the continued general acceptance of cash.