Cash in Kenya during the First Year of the Pandemic

Three in Four Kenyans Hold a Mobile MoneyFrom the Latin word moneta, nickname that was given by Romans to the goddess Juno because there was a minting workshop next to her temple. Money is any item that is generally accepted as payment for goods and services and repayment of debts, such as taxes, in a particular region, country or socio-economic context. Its onset dates back to the origins of humanity and its physical representation has taken on very varied forms until the appearance of metal coins. The banknote, a typical representati... More Account

Kenya is widely considered the poster case for how mobile payments can broaden financial inclusionA process by which individuals and businesses can access appropriate, affordable, and timely financial products and services. These include banking, loan, equity, and insurance products. While it is recognised that not all individuals need or want financial services, the goal of financial inclusion is to remove all barriers, both supply side and demand side. Supply side barriers stem from financial institutions themselves. They often indicate poor financial infrastructure, and include lack of ne... More thanks to being the cradle of M-Pesa. This mobile payments system has broadly been credited with improving Kenyan’s access to financial services compared to their peers in African countries such as Nigeria, Ghana, South Africa, and Egypt.

According to the World Bank’s Global Findex Database, in 2017

- 81.6% of Kenya’s population age 15 and older had an account at a financial institution,

- 37.6% of the target population had at least one debit card, and 5.7% had a credit card,

- 79% had made or received digital payments,

- 72.9% had a mobile money account, and 31.8% used a mobile phone or the internet to access a financial account

According to the World Bank’s World Development Indicators, in 2019,

- There were 103.8 mobile phone subscriptions per 100 Kenyans. The number increased to 114.2 in 2020.

- 22.6% of the population used the internet.

M-Pesa is not without problems, such as excessive indebtedness and criminal activities, including money launderingThe operation of attempting to disguise a set of fraudulently or criminally obtained funds as legal, in operations undeclared to tax authorities, and therefore not subjected to taxation. Money laundering activities are strongly pursued by authorities and in most countries, there are strict rules for credit institutions to cooperate in the fight against money laundering operations, to declare and report any transactions that could be considered suspicious. More, corruption, and ransom payments. Cash was (and still is) the underlying technology propelling economic growth in the leading African economies, well before the Covid-19 pandemic.

The Covid-19 Pandemic and the Kenyan Payments Infrastructure

Like other peer institutions in Africa, the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) decided to minimize the use of physical cashMoney in physical form such as banknotes and coins. More and promote the use of mobile money and banking solutions (Kenya Financial Stability Report, 2020: 38):

- Starting on March 16, 2020, the CBK waived charges for mobile money transactions of up to 1,000 Kenyan shillings (KES) through the end of 2020.

- The CBK also waived transfer charges between mobile money wallets and bank accounts.

- The CBK raised the transaction limits for mobile money from KES70,000 (USD621.12) to KES150,000 (USD1,330.97), and it removed the monthly total limit for mobile money transactions.

Regarding the payments infrastructure, by December 2020 (Kenya Financial Stability Report, 2020: 40-41):

- Credit and debit cards in the country had increased by 1.7% to 11.7 million cards.

- Point-of-sale terminals increased by 12.1% to 48,012 terminals.

- The number of ATMs declined by 47 to 2,412 ATMs.

CurrencyThe money used in a particular country at a particular time, like dollar, yen, euro, etc., consisting of banknotes and coins, that does not require endorsement as a medium of exchange. More in Circulation Grew Nearly 30% between September 2019 and September 2020

During the first year of the Covid-19 pandemic, Kenya experienced an increase in the precautionary demand for cash as a store of valueOne of the functions of money or more generally of any asset that can be saved and exchanged at a later time without loss of its purchasing power. See also Precautionary Holdings. More amid a crisis, more than compensating for the fall in the transactional demand for cash.

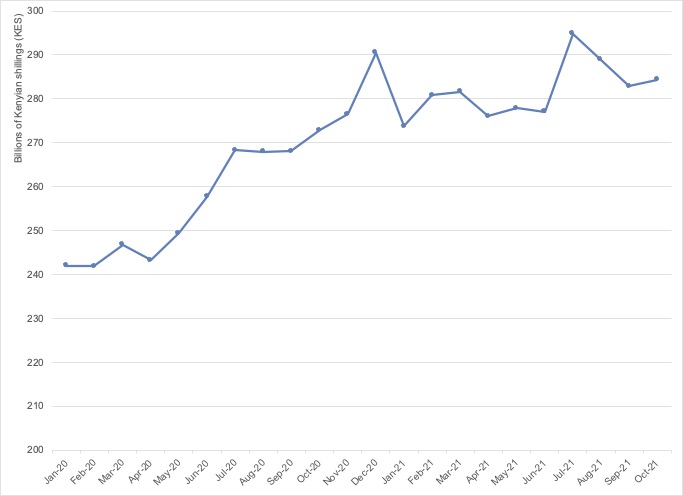

Currency in circulation in Kenya went from KES246.78 billion (USD2.19 billion) in March 2020 to KES281.586 billion (USD2.49 billion) in March 2021, an increase of 14.1% (see Graph 1).

The increase was even more significant (29.49%) if we compare the figures for September 2019 to September 2020: currency in circulation went from KES207.01 billion (USD1.84 billion) in September 2019 to KES268.12 billion (USD2.38 billion) in September 2020.

Graph 1. Kenya: Currency in Circulation, January 2020-October 2021

Source: CashEssentials, based on CBK Statistical Bulletin statistical series (2020: 11) and Monetary and Finance Statistics (2021).

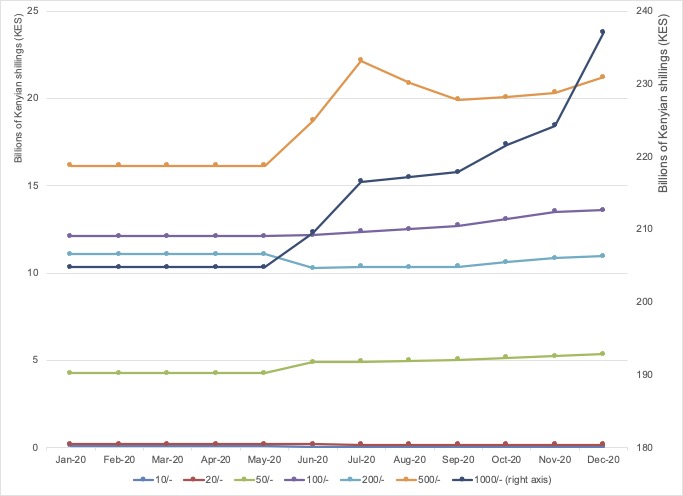

As with other countries, the demand for higher denominationEach individual value in a series of banknotes or coins. More banknotes increased markedly in Kenya during the pandemic. As can be seen in Graph 2, the volume of higher denomination notes grew dramatically between June and July 2020.

- The volume of KES500 notes (equivalent to USD4.44) stood at KES16.13 billion (USD143.12 million) in May 2020; then, it grew 16.09% in June 2020 and 18.35% in July 2020.

- The value of KES1,000 notes (equivalent to USD8.87) increased from KES204.79 billion (USD1.82 billion) in May 2020 to KES209.55 billion (USD1.86 billion) in June 2020 (a 2.33% increase) and KES216.53 billion (USD1.92 billion) in July 2020 (a 3.33% increase).

Regarding smaller denomination notes, the most notable growth occurred with KES50 notes (equivalent to USD0.44). The volume of KES50 notes grew 15% between May and June 2020, going from KES4.26 billion (USD37.8 million) to KES4.91 billion (USD46.57 million).

Graph 2. Kenya: Banknotes by Denomination, January 2020-December 2020

Source: Cash Essentials, based on CBK Statistical Bulletin (2020: 11), currency in circulation series.

Interestingly, fewer micro and small businesses reported that their customers were using mobile money for transactions in July 2021, compared to the lockdown period between April and July 2020, according to the CBK’s FinAccess MSE Covid-19 Tracker Survey.