ECB: The Covid-19 Pandemic has Amplified the Cash Paradox

More CashMoney in physical form such as banknotes and coins. More but Fewer Payments

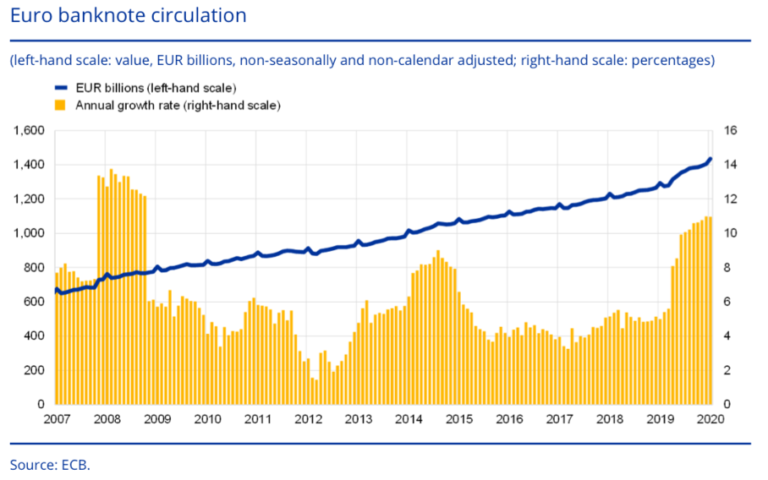

By the end of 2020, the value of banknotes in circulation in the euro-area reached €1,435 billion, representing an annual yearly increase of €142 billion or 11%. This is the largest increase since the 2008 global financial crisis, as many people in Europe have responded to the coronavirus pandemic by storing cash. Storing cash in turbulent times isn’t unexpected (Rösl & Seitz), however the size of the phenomenon and the fact that it coincided with a period during which cash payments were significantly reduced due to lockdown policies as well as efforts from governments, banks and retailers to nudge consumers towards digital payments (Beretta & Neuberger) do make it exceptional.

The European Central Bank (ECB) paper defines the cash paradox as an increase in the demand for banknotes while the use of cash for retail transactions appears to decrease. The trend is not new and is not exclusive to Europe. The ECB surveys on consumer payments show that the volume of Point-of-Sale (POSAbbreviation for “point of sale”. See Point-of-Sale terminal. More) and person-to-person payments (P2P) declined from 79% in 2016 to 73% in 2019. Other countries, including Australia, India, Japan, the United Kingdom, or the United States, have observed similar trends during the pandemic.

Understanding Cash Usage

The anonymous nature of cash makes it difficult to measure what drives demand. The ECB has adopted three indirect approaches to estimate the share of banknotes used respectively for three key demand components: transactions; store of valueOne of the functions of money or more generally of any asset that can be saved and exchanged at a later time without loss of its purchasing power. See also Precautionary Holdings. More, and international demand:

- The seasonal method is based on the monthly variations in cash demand and assumes that non-transactional demand dampens the seasonality.

- The return frequency method is based on the rate at which different denominations are returned to the central bank.

- The analysis of the introduction on the new Europa series and the rates at which the different denominations replace those from the first series.

Each approach has its limitations, and the reliability of the results depends on the assumptions employed. These models are also complemented by the ECB Study on the payment attitudes of consumers in the euro area (SPACE) , which provides a payment diaryAn increasingly used instrument by central banks, which consists in asking a representative sample of the population to record for a certain period of time all their transactions, as well as the payment method used. Payment diaries provide a snapshot of the use of different payment instruments. They are, however, a costly tool and do not provide real-time results, but are useful for comparative purposes. More for 2019 and another recent comprehensive study on the foreign demand for banknotes which concludes that between 30% and 50% of the value of euroThe name of the European single currency adopted by the European Council at the meeting held in Madrid on 15-16 December 1995. See ECU. More banknotes was held abroad in 2019. This share has been increasing in recent years.

The Three Components of Cash Demand

The report concludes that the share of the value of banknotes in circulation held for transactions is estimated to be between 20% and 22% in 2019. The store-of-value component accounts for between 28% to 50% of total circulation, and the foreign demand for euro banknotes represents the remaining 30% to 50. The wide intervals of the estimates indicate a high uncertainty since the ways people actually use cash are not directly observable. These estimates do not factor in the pandemic’s impacts, i.e., the decline in transactional demand and increase in precautionary holdingsBanknote demand motivated by the store of value function of banknotes, for saving purposes or as a precaution for uncertainties. See Hoarding. More. It will be important in the future to measure the long-term effects of the pandemic.

Based on these figures, it is estimated that each euro-area adult is holding between €1,270 and €2,310. However, the ECB stresses that banks are holding more cash and estimates that banks have increased their cash reserves by €30 billion since the ECB deposit facility turned negative in 2014. This represents nonetheless only 7% of overall cash in circulationThe value (or number of units) of the banknotes and coins in circulation within an economy. Cash in circulation is included in the M1 monetary aggregate and comprises only the banknotes and coins in circulation outside the Monetary Financial Institutions (MFI), as stated in the consolidated balance sheet of the MFIs, which means that the cash issued and held by the MFIs has been subtracted (“cash reserves”). Cash in circulation does not include the balance of the central bank’s own banknot... More.

A Paradox that leads to other Paradoxes.

The ECB emphasises the importance of the cash paradox for central banks in terms of retail paymentA transfer of funds which discharges an obligation on the part of a payer vis-à-vis a payee. More strategies, liquidityDescribes the extent to which assets or rights can be converted into cash without causing a significant decrease in the asset’s price. Accordingly, liquidity is often inversely proportional to the profitability of the asset and involves the trade-off between the selling price and the time needed to convert it to cash. In finance, cash is considered the most liquid asset and cash is sometimes used as a synonym for liquidity (e.g. cash reserves; cash pooling…). More management, monetary policy, and the financial system’s resilience. “If cash is widely used as a safeSecure container for storing money and valuables, with high resistance to breaking and entering. More haven during times of potential market turbulence, it may be mandatory to hold substantial strategic contingency stocks of banknotes to meet extraordinarily high demand during periods of crisis.” writes Alejandro Zamora-Pérez, author of the paperSee Banknote paper. More. But more broadly the cash paradox, also highlights other paradoxes for the cash community.

The first is that as we see more cash in circulation, the infrastructure to distribute, count, and sort cash is shrinking. Central banks have been closing cash centers, and banks have been closing branches and ATMs. The ECB SPACE study has highlighted the deterioration of the ease of access to cash as the level of satisfaction has dropped from 94% in 2016 to 84% in 2019.

The second paradox is that merchants’ acceptance of cash has been declining despite consumers holding more cash. According to the ECB IMPACT survey, almost 40% of respondents used less cash during the pandemic, and for 20%, this was due to merchants either not accepting cash or strongly advising not to use it.

The third paradox is that as the transactional use of cash is declining, numerous governments continue introducing policies to nudge consumers away from cash (Beretta & Neuberger). This includes, for instance, cash payment limitations present in seven euro-area countries, subsidies in favour of digital payments, obligations to accept digital payments, or limitations on legal tender.